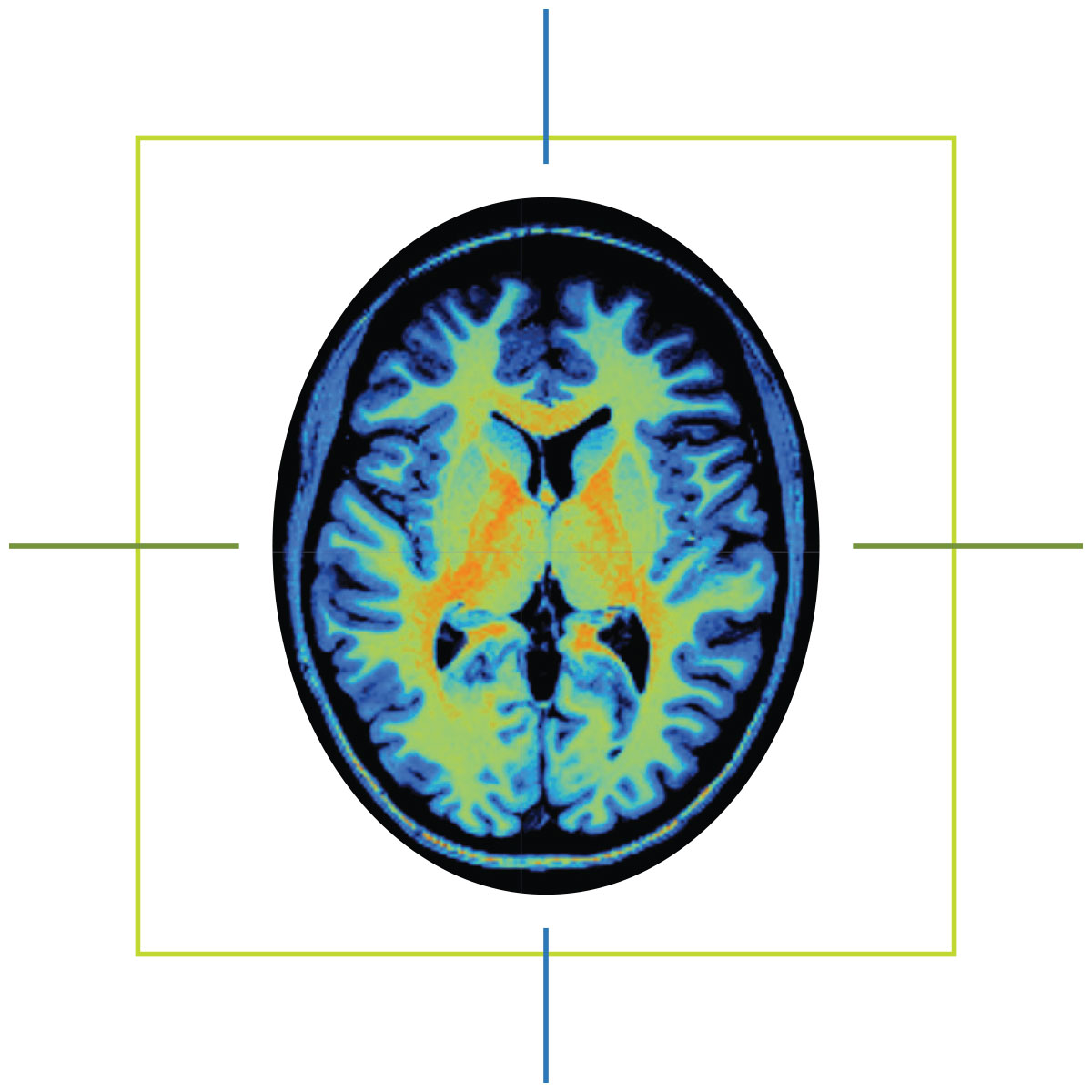

When Marcus Ryninger tells people how his life changed on May 1, 2015, he shows them an MRI scan saved to his phone.

Ten years ago, a massive stroke damaged the left side of his brain, leaving him with aphasia, a language disorder that affects communication. In the months that followed, Marcus and his wife, Marsha, found themselves at the University of South Carolina, where researchers from the Center for the Study of Aphasia Recovery performed an MRI.

Marcus knew recovery would mean teaching his right side to form the words his left no longer could. One of the university’s speech-language pathologists would work with him on that as part of his participation in an aphasia study.

He also knew his speech would never return to how it was before the stroke. But after seeing the scan of his brain — the dark hole of necrotic tissue on one side, the vibrant patchwork of healthy tissue on the other — the man who spent 30 years as a mechanic and quality control supervisor in the Navy understood: The stroke had not taken his determination.

“It helped me see what damage was done,” Marcus says. “I worked on airplanes. You have to find what’s broken and fix it. And the brain, that’s me. I know, ‘Oh, this part is broken. I have to fix this side.’ It made a difference for me.”

Before hospitals began using magnetic resonance imaging machines, or MRIs, for clinical use in the 1980s, physicians had a limited window inside the human body. X-rays could capture images of a patient’s bones. CT scans could even see soft tissues like muscles and organs. But both imaging methods exposed patients to ionizing radiation, and both were poorly suited to distinguish soft tissue variations critical for identifying ligament issues, brain anomalies and some types of tumors.

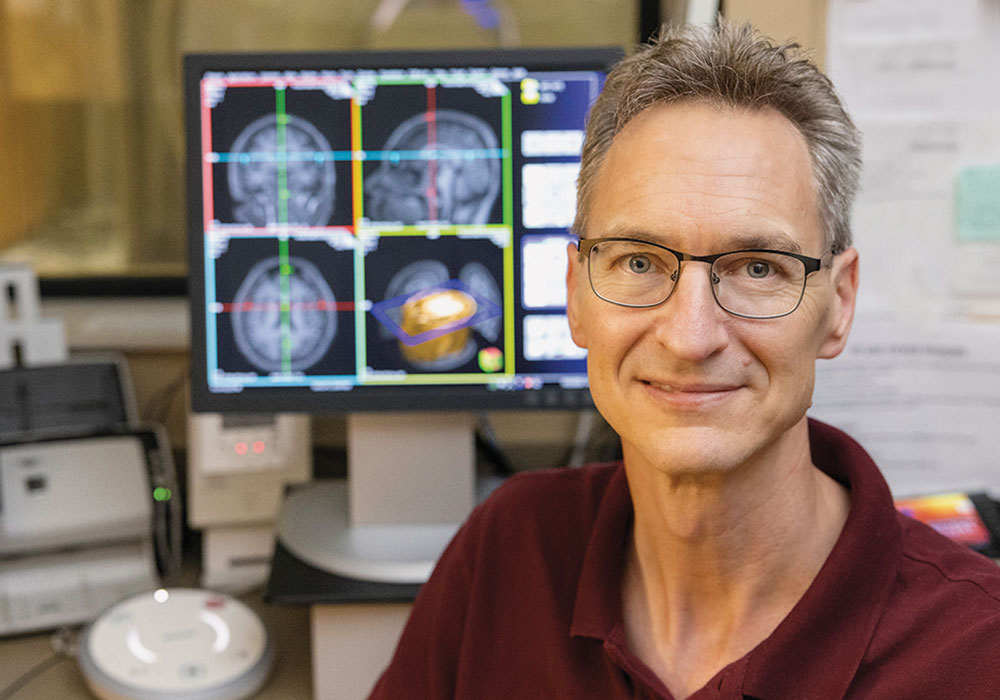

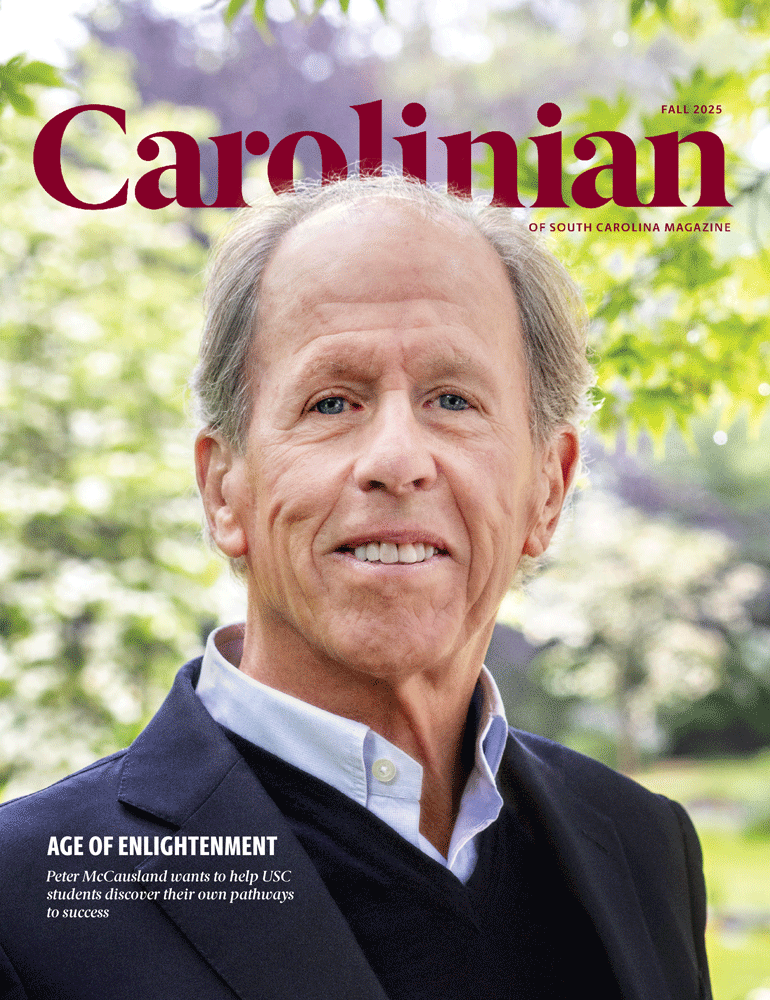

When the MRI hit the scene, it meant big things for clinical care — and for research. Just ask psychology professor Chris Rorden, whose Endowed Chair of Neuroimaging is funded by USC benefactor Peter McCausland. Rorden is co-director of USC’s McCausland Brain Imaging Center, home to the equipment used to scan Marcus Ryninger and thousands of other study participants since 2006.

MRIs are commonplace in hospitals today, but most have a magnetic field strength of 1.5 Teslas or less. The McCausland Center’s scanner is a 3 Tesla, twice the strength of typical MRIs.

“It really turned out to be a magnet to attract a lot of other people to come here, because we have an instrument that allows us to do cutting-edge research.”

Access to equipment of that caliber is something most researchers can only dream of. It has enabled the center to bring in tens of millions in grant funding and has led to an explosion in research studies that have advanced our understanding of aphasia, stroke treatment and brain aging.

Then there’s the appeal to prospective students and faculty. Rorden himself was drawn to USC by the scanner. The researcher, who earned his Ph.D. from Cambridge, developed the free neuroimaging visualization software that’s used by scientists around the world.

“It really turned out to be a magnet to attract a lot of other people to come here,” Rorden says, “because we have an instrument that allows us to do cutting-edge research.”

When Julius Fridriksson first came to South Carolina as a researcher 24 years ago, he was struck by the lack of neurology care and expertise in the state’s rural areas, often leaving stroke survivors and other patients in the dark. He still remembers the first study participant he scanned — she believed her loss of arm movement on one side was because of a fall, not her stroke.

“I started thinking, ‘None of this makes any sense to these people,’” Fridriksson says. “Why? When you go to most hospitals in South Carolina, outside of the big cities, you don’t get any expertise. You stay in the hospital as short as possible, and then you get discharged and there’s nobody to catch you. That was always in the back of my mind.”

Now the university’s vice president for research and the imaging center’s other co-director, Fridriksson has become a nationally recognized expert on aphasia and has conducted numerous studies using the 3 Tesla scanner. Since taking the helm of USC’s research office in 2021, he has pondered how to do more for brain health.

Fridriksson’s vision is for USC to become a national leader in brain health treatment and research. Two projects are quickly turning his vision into reality: the Brain Heath Network and the Brain Health Center. Both initiatives are led by Leo Bonilha, the university’s clinical director for brain health and senior associate dean of research at the School of Medicine Columbia.

The Brain Health Network is a rapidly expanding network of clinics opening in neurology deserts — rural counties where seeing a neurologist might mean a nine-month wait list and a two-hour drive. Primary care physicians, who often don’t have the specialized training to treat Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia, refer patients to the USC clinics for screenings and then receive a diagnosis and care plan.

“You can imagine, a wife brings her husband who is not sleeping through the night, is extremely disruptive, walks off during the day,” Fridriksson says. “It takes an enormous toll having to wait nine months, and that is not acceptable. But for us, the maximum wait for care is three weeks. We have a well-oiled machine.”

To date, seven clinics are in operation, thanks in large part to bipartisan buy-in from state legislators. Fridriksson hopes to open five more by the end of the year.

“It’s a real thing. It’s not fluff,” he says. “We’ve now completed more than 900 patient visits since we first started seeing patients. By this time next year, we’ll have seen thousands. It’s making a huge difference.”

If you think of those rural clinics as wheel spokes, Fridriksson says, the hub is USC’s new Brain Health Center. Slated to open next to Prisma Health Richland in 2026, this state-of-the-art building will house two more MRI scanners: the state’s first ultra-high field 7 Tesla scanner and a wide-bore 3 Tesla scanner that can accommodate patients with larger builds.

Both projects will help South Carolina anticipate the needs of its aging population, and Fridriksson envisions further expanding the scope of care to include movement disorders, epilepsy and other neurological conditions. Beyond improving care for South Carolinians, the network of clinics will significantly increase opportunities for clinical trials, a boon for researchers seeking to improve treatments. Fridriksson credits the McCausland Brain Imaging Center as a springboard for all of that.

“My idea for the Brain Health Network and the Brain Health Center would never have come about had the McCausland Center not been here,” Fridriksson says. “I’ve been doing my research on that scanner. I’ve been its primary customer as well as its director since 2006. There’s no way that would have happened without that center.”