To step into Henrie Monteith Treadwell’s Atlanta home is to flip through a well-worn passport. Colorfully painted figurines of African women strike poses along the fireplace mantel. The built-in shelves that flank either side of it display stout woven baskets, glossy ceramic vases, carved busts. The Columbia native is surrounded by mementos of a career that has taken her around the world and back.

Henrie Monteith Treadwell. If you’re in any way affiliated with the University of South Carolina, you may know the name. In the fall of 1963, she and two other Black students enrolled at USC, officially desegregating the state’s flagship public university. When she filed the lawsuit that led to that landmark moment, she was just 16 years old.

In 2024, a photograph from that moment became the inspiration for a monument that now stands on USC’s historic Horseshoe, just feet from the steps where she, Robert Anderson and James Solomon Jr. made history more than 60 years ago.

But since graduating in 1965, Treadwell has enjoyed plenty of other significant moments and milestones. She earned a master’s and a Ph.D. and then did postdoctoral work in public health at Harvard. Then there was her work with the Kellogg Foundation, which took her to rarely visited corners of the world. Most recently, she can point to the health advocacy organization she launched at Morehouse School of Medicine, where she has made significant strides studying and addressing health issues in marginalized populations.

“I became, I think, more or less a citizen of the world versus a South Carolina native,” says Treadwell, who moved from Battle Creek, Michigan, to Atlanta after the death of her husband in December 1998. “Some of my best learnings were in some of the African villages, particularly where they had very little but would always have some scalding hot water with tea and something to serve. Some would say, ‘Oh, you can’t eat that.’ I ate it. I didn’t get sick. I just ate it because we were coming together. I think we don’t come together as much as we should. We’ve got to learn to cross that bridge and just come together.”

More than Chemistry

For Treadwell, coming together is part of the Monteith family DNA. When she talks about growing up on her family’s homestead in Columbia, she often tells a story about her grandmother, Rachel Monteith, the family’s formidable matriarch.

“At night, she would hear something outside, and I would see her go past my bedroom door with a shotgun,” Treadwell says. “Occasionally, she’d shoot it off. You can’t unsee that. She had a steel spine.”

All the Monteith women did, and Treadwell learned by their example. Grandmother Rachel, who believed in improving educational opportunities for people of color, founded one of Richland County’s first Black public schools, a three-room building on North Main Street. Treadwell’s mother, Rebecca Monteith, taught at the school and eventually became principal. Her aunt Modjeska Monteith Simkins spent a decade as a director at the South Carolina Tuberculosis Association, where she fundraised and advocated for public health reforms within the state’s medically neglected Black communities.

In everything the Monteiths did, there was an unspoken expectation: Injustice necessitated action. Treadwell remembers her family sorting food and clothing donations for people who were terrorized after their involvement in Briggs v. Elliott, a local school segregation challenge that became part of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education.

“I think all of those things, the actions that they took in civil rights struggles, I was able to put a lot of things together in terms of what is needed,” Treadwell says. “People needed to be educated.”

That certainly applied to her own life. Public health wasn’t on her radar as an avenue to address societal needs when she entered USC. Instead, she studied biochemistry, a field that appealed to her inquisitive nature.

“I think I’ve always wanted to figure out how you get to the essence, the core of issues,” she says. “And that seemed to me at the time to be a way to do it. But I eventually determined that the issues that people are facing are really a lot more than just chemistry.”

Boots on the Ground

When Henrie Monteith graduated from USC, her path wasn’t entirely clear. The one thing she did know was that she wanted to continue her studies. Growing up in a family of educators and avid readers, she says, “it never would have occurred to me to not be interested in education and more education.”

So after getting married and accompanying her first husband to Boston, where he was working on a Ph.D. in physics, she decided to pursue a master’s in biochemistry from Boston University. Later, after moving to Atlanta, she earned a doctorate in biochemistry and molecular biology from Atlanta University.

She was chair of the mathematics and natural sciences division at Morris Brown College in Atlanta when a postdoctoral fellowship brought her back to Boston, this time to Harvard’s School of Public Health. Studying river blindness and elephantiasis, vector-borne illnesses commonly found in tropical climates, opened her eyes to the complexities of public health.

“I concluded that river blindness and elephantiasis will never be cured by simply having a medication, that we had to do something about water, water supplies, poverty,” she says. “We had to educate people about how to avoid the diseases.”

She also learned something else — about herself and her role.

“I was impatient with processes that were one-by-one when I felt that you could really affect community-wide issues so that many people would benefit,” she explains. “And, I must say, I just couldn’t see the direct benefit to communities because much of that research takes years and years and millions and millions in funding. From my perspective, I wanted to be more hands-on, more boots on the ground.”

Alabama, Zimbabwe and Beyond

If Harvard was an eye opener, the Kellogg Foundation was where her vision came into focus.

Headquartered in Battle Creek, Michigan, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation is one of the largest philanthropic organizations in the U.S. It funds grants and other efforts to improve social conditions, with a focus on helping children and families thrive. Shortly after recruiting Treadwell from Harvard, the foundation put her in charge of a portfolio of health-related grantees in the U.S.

When she describes a visit in the 1990s to an impoverished community in Lowndes County, Alabama — smack in the middle of the state’s Black Belt, so named because of the dark, dense soil that doesn’t play well with septic systems — you can see the murky wastewater being pumped directly into a resident’s yard through a length of PVC pipe connected to the side of an aging mobile home. You can smell the raw sewage.

But you can also feel her commitment. As a program director with the Kellogg Foundation, Treadwell visited sites like these to help fund solutions to pressing public health issues.

And her efforts weren’t limited to the rural South. Her work also took her overseas, where she encountered even more challenges but also more rewards.

Her first assignment in southern Africa, for example, took her to Zimbabwe, where she would eventually play a role in establishing a much-needed dental school. Subsequent assignments took her to Botswana, Swaziland (now Eswatini), the Dominican Republic, China and India, among other locations.

And Kellogg went above and beyond to ensure she had what she needed to succeed. When her colleagues found out that she couldn’t always afford the plane tickets to fly home to Atlanta, they arranged her travel and provided remote work technology decades before it was the norm.

“Not only did Kellogg support me; they felt that what I was doing was significant,” she says. “And so, they would often have me take teams of their staff on visits so that they could see what was being done — opening clinics in rural areas, opening schools in rural areas, all these things that you would think, ‘How does she know to do that?’ But somehow I did, and it worked. We would run away from the cape buffalo one day, or the elephants another day, but we’d get it done.”

Sometimes that meant helping women learn to weave baskets or raise livestock so they could support their families financially. Other times, she found herself surveying water infrastructure in Central American villages and coming away with ideas that could be implemented elsewhere.

The work had immediate real-world impact. The experience, meanwhile, helped her advance community health in ways that could continue long after Kellogg’s involvement.

No Matter What Else

When Treadwell thinks back to her family’s civil rights work, she says, there was little talk about what ought to happen; instead, they simply did what was needed.

“It was an example and an expectation that you do,” she says. “I think that’s one thing we maybe don’t have enough of — setting expectations to promote community justice behavior.”

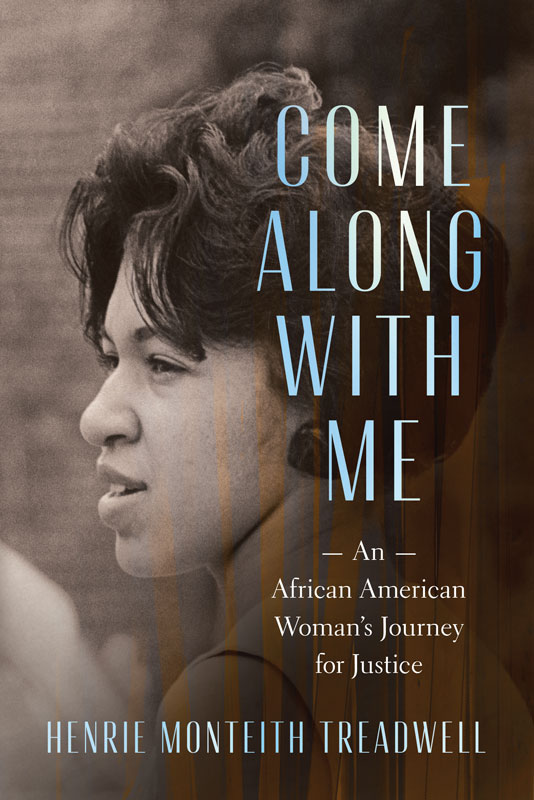

But while her role in USC’s desegregation was significant, it was also just one chapter in a long career. She revisited those memories while drafting her memoir, Come Along With Me: An African American Woman’s Journey for Justice, scheduled to be released by the University of South Carolina Press in the fall. She also had a chance to contextualize those events within the larger themes of her life and work.

Henrie Monteith Treadwell’s memoir Come Along with Me will be published by USC Press in October 2025.

“I have been, over these past 60 years, around the world, working in ways that really mimic what I did at the university,” Treadwell says. “It’s a way of opening doors for people who do not themselves have the key to that door. Taking the walk into the university was just an example of what I’ve continued to do throughout my career.”

Now in her 70s, she is the founding executive director of the Community Voices project at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta. The work grew out of her 17-year tenure at Kellogg, where she was part of Community Voices: Healthcare for the Underserved, a multimillion-dollar health initiative with project sites across the country. The job change came at the urging of her children, who recognized her desire to stay in public health but also wanted her to move back to Atlanta after the death of her husband, Harold Treadwell.

Since coming to Morehouse in 2003, she has conducted and published research in areas where it is desperately needed, homing in on topics such as men’s health, oral health care in poor communities and health concerns in the prison system. Much of her work boils down to strengthening families, particularly in Black communities, where issues such as high incarceration rates in men disrupt the family structure and perpetuate the cycle of poverty.

She spends time mulling over how problems like these can be solved, how policymakers can be moved to act. But, true to her guiding values, she believes the solution lies not in pointing fingers, but in appealing to our shared humanity and seeking partners to do the work that needs to be done.

“In order to reach that goal, it’s not just putting new things on the ground, but it is also informing, advising, educating policymakers,” she says. “That’s one of the hardest things we have to do in this volatile environment that we have had for many years in this country. But you do find that there are people who want to and are willing to go in different directions, but it’s going to take some time. It takes continuing on the path no matter what else is going on.”